Over the past two weeks, Ben and I had 2 clinic mornings without a preceptor (Elizabeth was fulfilling her teaching duties at the College of Medicine). Of course, these mornings had some of the most acute patients that required quick management and transfer to the central hospital in an ambulance. Without telling you all the details, the patients included 1-2 patients who were probably psychiatrically unwell (I realized I don't know much about how mental illness manifests in Africa or Malawi), a patient with HIV/TB and pneumonia, a woman having a 20 week miscarriage, a woman with abdominal pain and sepsis (or severe malaria and we missed it), and a woman with sepsis likely from postpartum endometritis. As I am slowly learning more, I have realized how important it is to have a significant knowledge of the culture and the ways that diseases manifest, in addition to how to treat them. A month is much too short to do this well! In addition, knowing how to correctly diagnose and treat common conditions in Malawi is only one part of the entire picture.

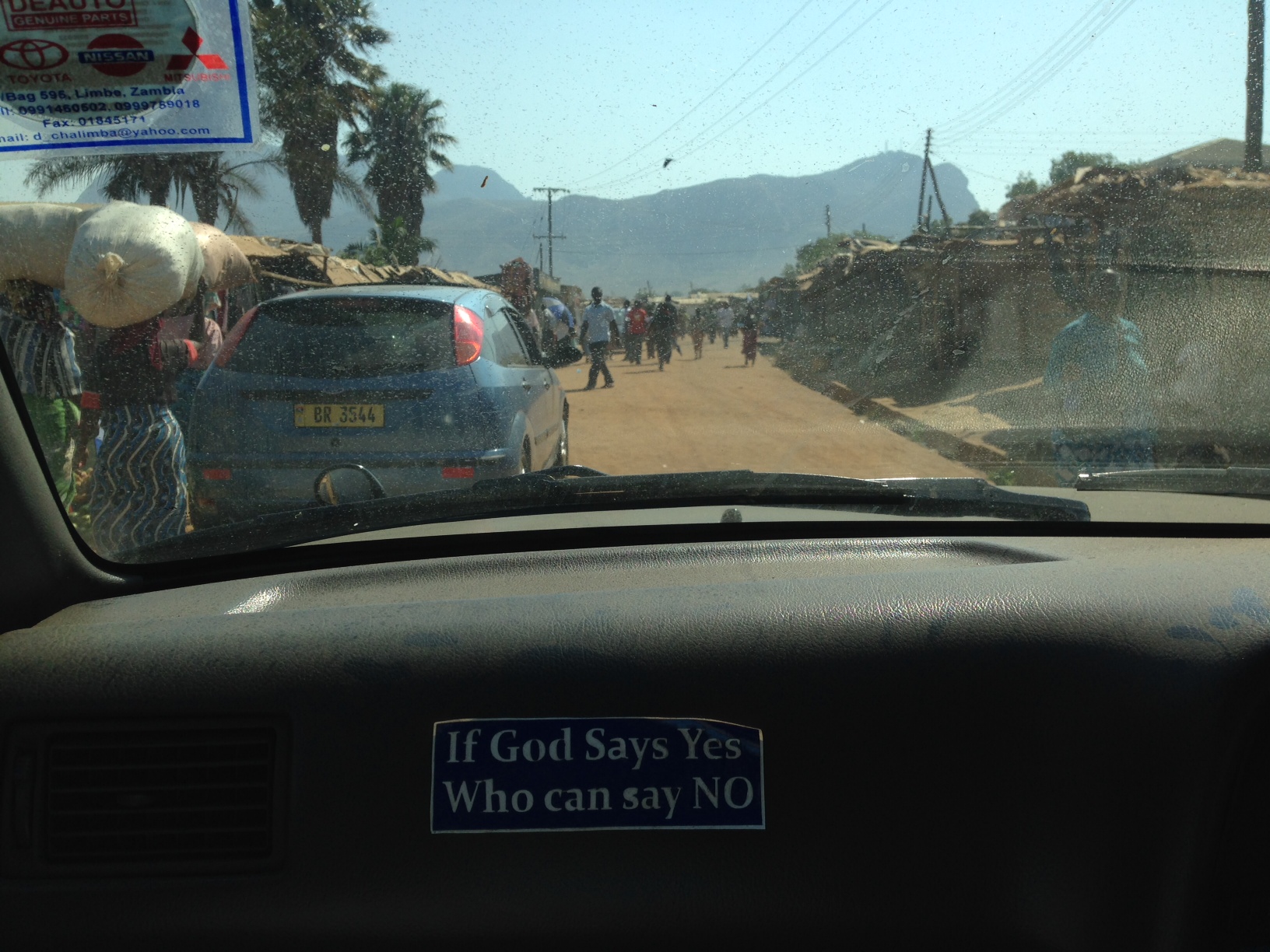

The story of the woman mentioned above with abdominal pain/sepsis vs severe malaria encapsulates so much of Malawi health care. I initially saw her lying on the ground in the fetal position in the large courtyard between many of the clinics where different services are provided. Problem/observation number one: sick woman is lying on the ground. I was attending to another sick patient at the time, so the next time I glanced her way she was sitting up, breastfeeding. I surmised that she must be feeling better than she initially looked but actually, I was just observing problem number two: sick woman continues to care for her child rather than seek immediate help. I next saw her sitting closer to our clinic door, so I went out and instructed her to go get a rapid malaria test. She collapsed after a few feet. Problem number three: there are not enough health care workers to assess/triage someone who might be too weak to walk safely throughout the health center. We moved her to the short-stay unit, we took a few vital signs, did a rapid malaria test (negative --though we can't rely on this negative result in someone so sick) and found she had severe abdominal pain. Thankfully, an ambulance was already there to pick up another patient, one with HIV/TB and likely pneumonia (the ambulance had taken a good 45 minutes to arrive for him), so we added her to the pick-up request. Problem number four: our patient was going to have to ride in an ambulance with a patient with TB --so we gave her a protective mask. Problem number five: the ambulance didn't just contain the TB patient, it also contained about 6 other patients stuffed into the back of a van (one of whom was stretched out, stiff --my differential diagnosis for him at a glance included tetanus vs rigor mortis). The protective mask seemed ridiculous now. The patient's mother was now carrying the patient's small child and wanted a ride to the hospital as well. There aren't enough nurses for patients at the hospital, so each patient needs a "guardian" at the hospital to feed and bathe them and do their laundry. Problem number six: the baby was going to ride to the hospital and be exposed to several sick patients including one with active TB and one who was quite possibly dead, so that grandma can be there to support the patient.

Of course, there are a few admirable aspects of what I just described -- the heartiness of the woman who was still breastfeeding even though she was too weak to stand. The family support around ill patients who require guardians in the hospital. But there are too many unfortunate realities that make substantial improvements in safety and quality of care a very distant goal, even if we have impeccable diagnostic/treatment skills.

On to another topic: Ben and I just attended two days of malaria training --this is extremely relevant to the health care workers here because the protocol for treating severe malaria has recently been modified. Furthermore, our instructor reported that in a small survey of 30 health care workers in hospitals across Malawi, only one person was able to correctly identify a case of severe malaria. This mandatory training is part of an effort to expand the education of the Malawian health care workers to improve identification and treatment of severe malaria -- and it was extremely important for us to hear too. Given that we rarely see malaria in the United States, we have a poor understanding (beyond basic book knowledge) of when to suspect malaria, especially in the absence of our usual battery of tests. As mentioned above, in the course of the training, I started to think of several patients whom (based on what we were learning) we should have treated empirically or presumptively for malaria. I feel humbled that, while there have hopefully been some patients whom we have helped by being here (and I hope we are helping/contributing with Elizabeth on a larger scale), there are probably some patients we haven't helped or those we have even harmed by our inexperience and lack of knowledge. This point represents why participating in Global Health can be so hard, complicated, nuanced.

On another note, our class was enjoyable/curious for numerous other reasons.

-We had a few singing stand-up/sit down breaks initiated by adults in the class (almost likeSunday school -- it was actually a song I remembered from Sunday school!).

-Though the class took place at a government hospital, there was an opening and closing prayer.

-It was fascinating and amusing to observe what points of lecture became points of argumentation between students and lecturer. To Ben and me they seemed to be the most minor points (for example, how do you place a suppository? was that sentence on the powerpoint worded correctly?) but they would often unexpectedly cause a prolonged quarrel in the class.

-The instructors used powerpoint but also a large paper/marker in the front of the class. They used this for drawing examples of what might be seen on a microscope view of a malaria slide (it would seem much easier to me to just put one picture slide in the powerpoint of the actual malaria smear - since we had powerpoint and video etc. But instead, large red circles were drawn with marker on a poster).

-Our classmates were called on individually to answer questions (we were spared this, mostly). One classmate was a large somewhat sweaty man -- well, we were all sweaty, it was around 90 degrees - named Precious.

-There was AC in the room and when it was functioning well on day two (finally Ben and I were comfortable), the ladies were wrapping themselves in their chitenjes, (their multipurpose skirt/shawl/baby carrying wrap) to keep warm. I was not even close to chilled!

In terms of the advancement of Ndirande health center, we had a few successes. We led a teaching session last week that received good reviews and actually felt like it opened the door for some further conversation and camaraderie. I had a call night with Loveness, a very talented clinical officer who loves obstetrics and with whom I felt a bond of friendship almost immediately. Clinical officers take overnight call often, though usually from home, and this was her first time sleeping at a "hospital" (I reflected that I have slept --or not slept - overnight at the hospital at least 100 times). We saw 10-15 patients of variable acuity -- some of whom needed immediate stabilization and transfer to Queens hospital, some of whom we kept overnight to monitor. Lots of malaria, probable meningitis and florid pneumonia. Loveness ran the show and I assisted her (contrast this to Ben's call experience from a previous post). What was encouraging to me about working with her is that she too is passionate about improving Ndirande and had previously worked at a site that was much more organized (imagine, a nurse taking vitals and triaging patient acuity and an organized system for storing medication and tracking their use). Though Ndirande has been our only exposure to health care in Malawi, and though resources are slim and facilities overcrowded most places in Africa, it seems it is not the norm for health centers to be in such chaos and disarray as Ndirande. Loveness has vision for applying improvements based on her past experience, though she too is nervous about being an "outsider" or a newcomer who is pressing for change. But as she said, the change will come, "by and by," and I am thankful there are numerous people from various angles rallying to support this place.

I have to admit, the mosquitos and the heat are getting to me, I'm looking forward to coming home! Though it's more arduous, there are some sweet aspects to life here. Liam (Elizabeth's 10 year old son) had great perspective - when the water is out (happened 5 times last week), or the electricity is off (happened 2-3 times last week), you are unintentionally given something to look forward to (return of convenience!). When we were enjoying particularly soft bread (in contrast stale Malawian bread texture) at a dinner gathering, I overheard a girl say, "That's what I love about living here -- you'd never take notice of this bread's texture if you were in the (UK/US/developed world)." I think I still notice the great texture of Dave's Killer bread, even in Seattle, but I do agree that I have a new level of thankfulness for the simple things we enjoy so readily at home.

Amanda is here now, we greet Kannie tomorrow, and we have an African adventure planned for the next few days! See some of you back home :)

-Beth Thompson R3